READING AND OTHER VISUAL STUFF

/

According to surveys, print books are still not being replaced by e-books, even in this digital age. In spite of the availability of e-readers and the lower price of e-books vs. paper, most of us still prefer to have the hard copy version. Studies have shown that our memory of the things we read is better if we’ve read a hard copy. Researchers think it’s because our spatial memory comes into play—we picture where the desired information was placed on a page. For example: if we’re asked to remember what car James Bond was driving in a particular scene in a book (presuming his Aston Martin is in the shop) we may recall seeing that information in the second or third paragraph of a left-hand page. We can vaguely picture the page so we find it easier to recall the words in that spot. If we want to remember what his latest Bond girl was wearing…no, scratch that, they never wear anything for long. But the point is that e-books don’t offer the same visual cues, not to mention assorted other sensory elements like the feel of good paper, the smell of fresh ink, or the actual weight of an epic novel, that impact the pleasure of the reading experience.

It made me think about the future of data entry and retrieval. Will physical keyboards and text on a screen really vanish, as so many science fiction movies seem to suggest? I suspect that something like the hard copy reading effect will apply.

Futuristic films and TV shows often show people moving their hands through the air to interact with large 3D screens or holographic displays. Think of the Tom Cruise movie Minority Report or Marvel Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. on TV. Much of the technology is already available. Will such things really take over from clunkier input devices like keyboards? I’m not so sure. I think physical cues are important. Often when I’m typing I’ll realize that I’ve hit the wrong keys by misteak mistake by the feel, maybe even the sound, before I see the error appear on the computer screen. I also know that using a holographic display in a room of co-workers, there’s a good chance I could miss a key piece of data if it appeared in front of the office hottie walking by in a tight skirt.

When I watch Star Trek reruns, part of me says every member of the bridge crew should be manipulating holo displays instead of buttons and dials. But really, projecting technological progress two or three hundred years into the future, there would be no bridge crew at all. The captain would just tell the computer where to fly the ship and who to shoot at. Not much fun to watch on TV. I can’t see us making the choice to go that way either.

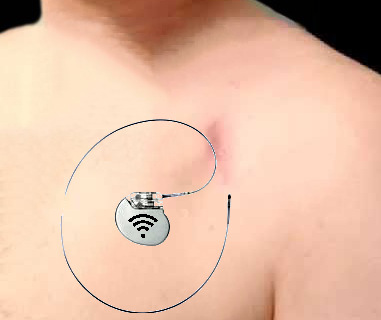

Star Trek’s holosuites take virtual reality to the limit, but don’t expect holographic presentations to offer stimulation to our senses of touch, taste, or smell anytime soon (chairs you can sit on and cars you can drive? Don’t think so.) For that the computer simulation will have to hack directly into the sensory centres of our brain to control what our brain thinks we’re touching and tasting, seeing and doing, whether we’re standing, sitting, or lying down. A full-body sensory illusion. While that could very well be possible within the next century or two, I’m willing to bet that frequent use of such tech would be a serious mental health hazard, causing us to lose our ability to distinguish between reality and simulations (a half-hour of being James Bond a day—that’s my limit).

The truth is, we’re wired to orient ourselves by sensory cues from a physical environment, and to judge our progress by the extent to which we affect that environment through our actions. Millions of years of evolution made us this way, and it will take a long time to change that. I don’t think we’ll truly want to.

For now, I’m content with my keyboard and screen. Just don’t ask me to go back to my Underwood typewriter.