PRIVACY SURRENDERED

/

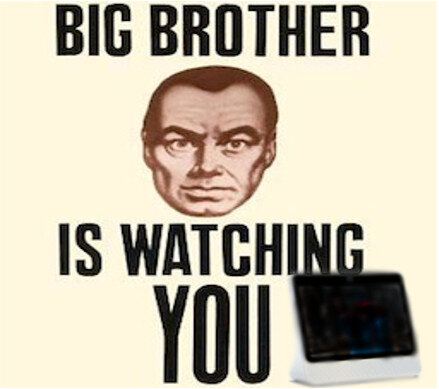

At a time when everyone’s offering their forecasts of what the new decade will bring, there are so many fronts one could explore. But over the holidays I was struck by how often one subject came up in conversation: surveillance technology. Not so much the kind forced upon us, but the kind we’re willingly embracing. Siri and Alexa. Google Nest. Facebook Portal. Some of us are willing to have internet-connected devices listen and watch us 24/7 for those times when we want to give a command to turn on a light, turn up the thermostat, place a call, or play a game that reacts to our physical movements.

Used to be that a peeping Tom had to sneak up to our windows. How times have changed!

I’m not a luddite—I use my laptop and smartphone constantly—but I have been known to put masking tape over the laptop camera and I’ve turned Siri off on both my Mac and iPhone (I’d never had the “Listen” feature activated anyway). Does that mean I’m now confident that my devices aren’t listening and watching? Not really. I’m counting on being too old, boring, and frugal to be of interest!

But isn’t it cool to think that you can just talk to your house and appliances and have them do the things you want without lifting a finger? Of course it is. And almost all of that functionality could be accomplished with a purely local non-connected system. Except that wouldn’t let the tech giants gather and sell information about you, and that’s how they make a big chunk of their money. As a wise person has said, if you’re not paying for a product (or you’re paying much less than its worth) then you are the product.

Along with all of this potential surveillance at home, there’s increasing use of closed circuit cameras and facial recognition in buildings and the streets of major cities (and smaller centres the moment they can afford it), police and military drones, and ever-more-advanced optics in reconnaissance satellites, so true privacy will be as rare as [insert your own joke about virgins here].

I see no signs of this trend ending anytime soon—privacy legislation is being enacted, but can laws protect the privacy of someone who willingly gives it up? So my crystal ball says that by the end of this new decade the feeble struggle will have ended and society at large will have fully accepted that Big Data companies, governments, and faceless tech employees can see and hear everything we say and do, anywhere anytime. No big deal. Right?

What will this look like? Well, of course, the reason companies want to know so much about you is so they can sell you things, and by the end of the decade all advertising will be personalized advertising. Compliment a friend on their choice of jeans and a moment later your devices will be showing you how and where to buy them. I know people who’ve already experienced something like this, even when their phones have been locked. In ten years it will just be assumed. Store signs you pass will point out that they stock the product you were looking at on the person who just walked past you (thanks to eye movement analysis). If you still read physical magazines and linger over a particular ad, your favourite device will add that product to your wish list with a helpful link to the retailer who placed the ad. Your fridge will reorder groceries automatically based on not only your regular use but also your plans to entertain, host a kids’ sleepover, or go on a trip. Your home office will reorder supplies. So will your bathroom.

This personalized marketing will surround you in cars as well as your home, whether it’s a private car or, more likely, a shared ride or Uber-type vehicle (self-driven, though). And don’t worry about having to rummage through your purse to find a payment card. Apps will know the expression on your face when you’ve decided to buy something, and they’ll take it from there. Your closets and cupboards might remind you about articles you’ve bought and aren’t using, but you’ll be able to turn that function off, because who likes a nag anyway?

It also goes without saying that, even without posting on social media, all of your friends and acquaintances will know what you buy because that just might convince them to buy it too. You’ll be OK with that, because it’ll all be part of the social status game that no one will be able to avoid without going off to live in a cabin in the woods.

Buying things won’t be everything there is to life…not quite. People will still do other things in their homes and cars, and companies will find ways to monetize that. The most obvious way is pornography. Yes, I mean starring you. In ten years companies will no longer even pretend that they’re not recording and storing the things you do that might interest other people, and sex will be at the top of the list. Mind you, they won’t want you trying to sue for a cut of their profits, so they’ll probably use “deep fake” technology (already very advanced) to alter the appearance of you, your partner, and your home. Not only will such “amateur porn” be in demand, and accepted, but people will enjoy the game of watching it to see if they can spot themselves or others they know. After all, they’ll be able to set a preference for local subjects, maybe even neighbourhoods, just like the Find Friends apps you use now.

Bedrooms aren’t the only places people get intimate, and by 2030 most cars on the road will be self-driven. Freed of the burden of having to drive themselves, people will do other stuff. Though the fad will probably ease off after a few years, there will be an exuberant competition to see who can do the most outrageous things in their cars. Sex too? Of course!

Won’t all of this surveillance make us safer? How will criminals get away with anything when somebody’s always watching?

I think it’s pretty obvious that, as technology advances, so will the means to spoof or defeat it by those with enough money, like organized crime organizations. Or there’s always the low-tech method: bribing underpaid employees with access to all these feeds. One thing’s for sure, every item of value you own, your home and business addresses, your schedule, and your real-time location will be available at any time. Not to mention every other form of personal information imaginable. What more could a criminal ask for?

Is this just far-out paranoid conspiracy theory stuff? I only wish. Since much of it is already feasible, I’m probably being too conservative.

We’ll know in ten years. Maybe sooner.