LHC LOOKS FOR PARALLEL UNIVERSES

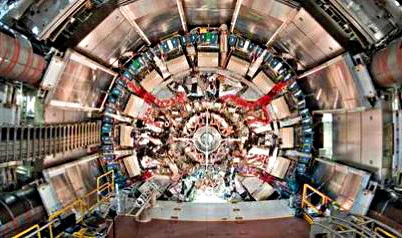

/If you read about a super high-tech science facility smashing atomic particles together at fantastic speeds and you picture a growing black hole that devours the Earth (!)…you might be a science fiction writer. Either that or a B-movie addict. Or a protestor at the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland.

In the coming weeks the LHC will do its best to produce some black holes, but they’re not mad scientists planning to destroy the world. Really. What they are hoping for is evidence of parallel universes. As in, universes that exist beyond the four dimensions we know (length, breadth, height, and time). New theories suggest that gravity may leak from our universe into other dimensions (and is the only thing that can travel between them) and the experiment at the LHC is looking for the proof. If microscopic black holes are produced/detected, they will be evidence of the existence of these parallel universes.

Don’t confuse this with the “multi-worlds theory” of quantum mechanics from Hugh Everett in the 1950’s. That theory claims that slightly different universes are being spun off every moment because of all of the possibilities that can exist when a traveling particle comes to a fork in the road and goes both ways. (That idea has inspired lots of alternate history stories and TV shows like Sliders, but it’s not provable.) No, a researcher with the new LHC experiment describes the parallel universes they’re looking for as if our universe is a sheet of paper in a stack of many more sheets of paper.

Of course, I’m always looking for the science fiction take on stories like this. The giant Earth-gobbling black hole is one possibility (and worried enough people that they filed lawsuits to try to stop the Large Hadron Collider from being built). But the idea of micro-miniature black holes intrigues me too. Imagine a series of mysterious deaths in Geneva and their corpses are found to have microscopic tunnels like wormholes tunnelled through them! Of course one of the victims would have to be the lover of one of the experiment’s lead scientists—just to add extra emotional depth, don’t you know. Or maybe gravity goes weird and the city starts looking like the famous M.C. Escher lithograph “Relativity” (with no consistent up or down). What if the combination of the LHC’s magnetic field and the black holes pulls asteroids out of space into collision with Earth? (Some conspiracy theorists are apparently already claiming this.)

Parallel universes offer even more fodder for imagination. Maybe our own universe originally came from one of those. Or perhaps life originated there instead of here. Or perhaps we somehow go there when we die.

OK, OK…most of these are still sounding like B-movie ideas, but you have to admit that the thought of protons smashing together at 99.9% of the speed of light with energies of nearly 12 Tera electron volts does fire the imagination.

The likely reality? The LHC team will detect some things never seen before and add to our knowledge of the universe. The world won’t even hiccup. And that’s good too.