WHY A.I.?

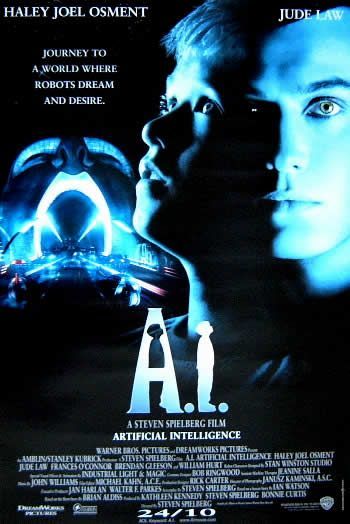

/ So much has been said and written about artificial intelligence (not to mention movies with Haley Joel Osment). What is it, really, and do we even want it? You’d be content with just finding some human intelligence once in a while, right?

So much has been said and written about artificial intelligence (not to mention movies with Haley Joel Osment). What is it, really, and do we even want it? You’d be content with just finding some human intelligence once in a while, right?

Computer scientists seem obsessed with trying to create machines that can think as well as human beings can. It sounds like a lot of trouble to create…a lot of trouble.

Back in June I blogged about a chatbot named Eugene that had supposedly passed the Turing Test by fooling a panel of judges into thinking they were conversing with a human being. It was a very clever trick, but surely not real artificial intelligence in the sense of a synthetic processor that is the mental equivalent of a human. Engineers and programmers can create specialized machines that can outperform humans in any number of areas, except it’s our very non-specialization that makes us special. Any given day we can get ourselves cleaned and dressed, cook and eat breakfast, drive a car to work (and fix a flat on the way, if necessary) where we might teach a class of students about literature in another language. We can discuss geopolitics in the lunchroom, shop for groceries on the drive home, all the while humming a favourite song or even imagining a Stones hit as it might be sung by Frank Sinatra, just for fun. Computers can have software installed to perform a task. Humans use evolved software (memes, instincts) to learn new software (skills) and adapt it to changing needs in ways that might never have been foreseen.

Some experts insist that, as computational power increases, machines are bound to be able to outdo the processing power of the human brain, maybe very soon. Such claims depend on estimates—no-one really knows how much processing the brain accomplishes. Reputable scientists have speculated that the human brain might be a type of quantum computer, in which case potential processing power increases enormously.

We should also make the distinction between intelligence and consciousness. Raccoons are smart (damn them) but we don’t know if they’re conscious. The thing is, no-one knows how consciousness works either, so how can we reproduce it in a machine? Many researchers just seem to assume that, once processors finally get fast enough, consciousness will appear. Maybe it will. But also maybe not.

It’s not impossible to imagine conscious machines—heck, when we’re kids we imagine that our teddy bears have personalities. We anthropomorphize all kinds of things, convinced that our car somehow knows when we get paid a bonus at work, and that storms deliberately target our picnics out of pure malice. The Cog artificial intelligence project at M.I.T. involved a humanoid robot, based on the idea that a machine intelligence could become more human-like through a very large number of interactions with humans, and that a human-looking robot would be more natural for humans to interact with. They might have been right about that, but the project is no more.

We know that every single human being we encounter has a rich inner life of desires, regrets, expectations and speculations, fears and dreams. Is that really what we want from our machines? What purpose would it serve? In fiction, when machines have desires and aspirations it becomes inevitable that those desires will eventually conflict with our own. That’s when the trouble starts. Skynet and its henchmen…er, henchrobots. So why go there?

Let’s be content with producing computers that process information very quickly and problem-solve within carefully thought-out limits. And let sleeping cogs lie.